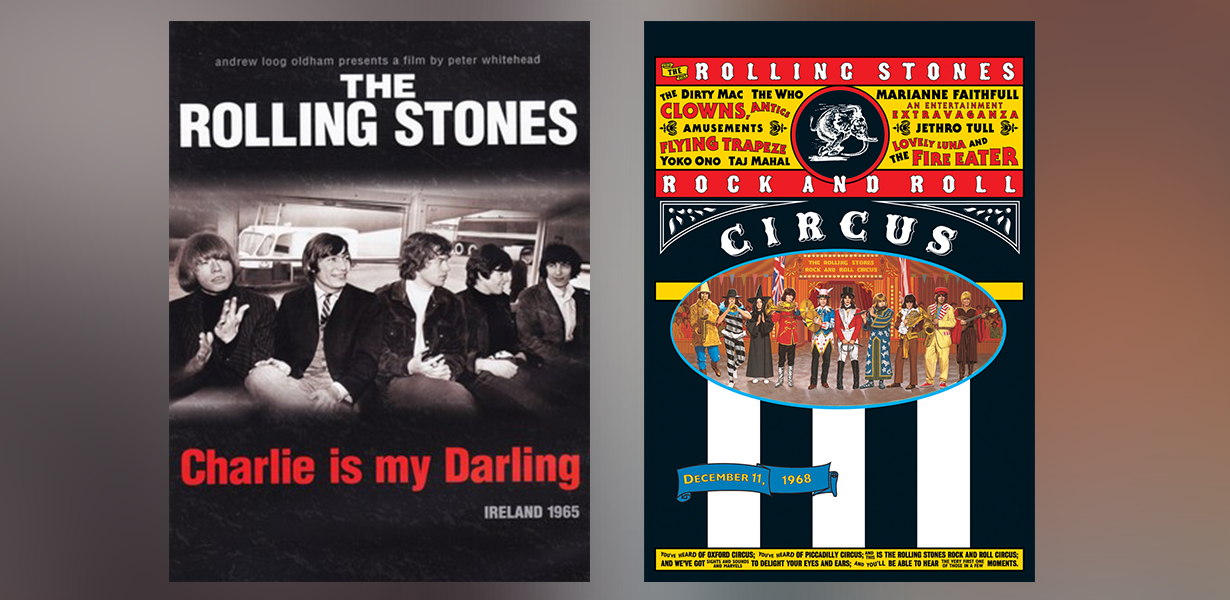

Charlie Is My Darling is both the best Rolling Stones documentary before Gimme Shelter and the best since, a neat time-travel trick that comes of marshaling nearly half-century-old material into something thrillingly new. In September 1965, avant-garde-ish filmmaker Peter Whitehead tracked the band whirling through Belfast and Dublin on a two-day tour just after “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” powered up the charts. His 35-minute verite doc won a festival award in Mannheim and was promptly replaced by a 50-minute version cut by Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, which was never released.

Helpfully distinguished from the much-bootlegged earlier version by a date stamp, Charlie Is My Darling – Ireland 1965 is not just a restoration but a reinvention, deftly reassembling Whitehead’s footage into a portrait of the Stones in a singular moment between pop stardom and rock god-dom. (The title, incidentally, refers explicitly to a traditional Scottish song and implicitly to Charlie Watts’ sweet-natured interview in the film.) More than half of its hour-and-change consists of previously unseen material, including 20 minutes of scintillating live footage. Director Mick Gochanour and producer Robin Klein – heading up the project as part of ABKCO Films’ drip-drop release of the mass of Stones stuff in its vault – wisely add no contemporary frame. Carrying none of the backward-looking, self-mythologizing weight of, say, Shine a Light or Crossfire Hurricane, Charlie Is My Darling packs a jolt of immediacy that from the first-minute burns through nostalgia and the fixed mental image of today’s desiccated, Olympian Stones.

That’s something I’d have thought impossible at this late date. This film’s spell lies in capturing the Stones almost but not quite yet fully formed, just becoming aware of their astonishing power. They take tea on a train, pleasantly tolerate gawkers, crack wise in the headspace between antic and bored. Unguarded but camera-aware, Mick Jagger and and Keith Richards work out what would become “Sitting on a Fence” before breaking into a goofy Beatles pastiche. Mick, baby-faced but with a whiff of the economics student still about him, coolly dissects his act and the galvanic social and sexual changes to come. Brian Jones, beautifully fey and faintly pretentious (“My ultimate aim in life was never to be a pop star”), frets about the future, already seeming not made for this world.

Onstage they’re electrifying, joyful, a great rock ‘n’ roll band not yet burdened with being the World’s Greatest Rock ‘n’ Roll Band and the gestures that entails. And as they steam through “It’s Alright” in Dublin, a horde of boys leaps out of the audience and rushes the stage, bowling over the cops and nearly taking out the bewildered band. Not out of any apparent provocation or protest, but because something about the Rolling Stones seems to give them permission. That we know the rest of the story and they don’t gives this film an exhilaration, prescience, and poignancy no retrospective music documentary could muster.

Three years later, in December 1968, the Stones gathered some friends (Jethro Tull, Taj Mahal, Marianne Faithfull, the Who, John and Yoko) in a North London TV studio for a dress-up rock variety show that chronologically and psychically occupies a place somewhere between Sgt. Pepper and Altamont. The band abandoned The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus unaired, dissatisfied with their performance (and, rumor long had it, irked at being upstaged by the Who). The show remained a misty legend until ABKCO rescued it decades later; now it’s a larky, entertaining, and, for a couple of stretches, riveting curio of a time when rock musicians could commandeer an hour of BBC time to do whatever the fuck they wanted.

Like mount a Victorian circus complete with big top drag (Charlie looks miserable), fire-eaters, and oddly old-looking acrobats. The studio audience are decked out in colorful ponchos and silly hats. Tull gets things off to an aptly clownish start, but the Who are indeed titanic, unleashing a towering “A Quick One (While He’s Away),” their alchemy of frenzy and control never better captured on film. Lennon fronts an impromptu supergroup dubbed the Dirty Mac (Eric Clapton on guitar, Keef on bass, Mitch Mitchell of the Jimi Hendrix Experience on drums); after a yowling “Yer Blues,” he retreats with a shit-eating grin for a 12-bar vamp above which Yoko shrieks. The audience reaction is not shown.

As Pete Townshend recollects in a DVD-accompanying interview, production disorder delayed the Stones’ set until nearly dawn. At first, they seem dead on their feet, opening with a lethargic “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and hanging on grimly through several tracks from Beggars Banquet, which had just been released. Little by little Mick regains his traction; by the time they reach “Sympathy for the Devil” he still seems bone-weary but in a different way – like a man at the end of his tether, clawing up his very last reserves. His body hot-wired to the congas, his voice raw and hectoring, he seems desperate not so much to play the song as to survive it, or flail it senseless. It’s a stupendously fearsome performance. Circus isn’t the historical document Charlie Is My Darling is, but at times it is as redolent of its moment, or of the moment about to come. At this one, those poncho’d hippies suddenly seem very out of place.

The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus screens May 30 as part of the Sound of Music vintage music film strand at the Krakow Film Festival.

Written for MusicFilmWeb

By Andy Markowitz,