It’s hard to overestimate the importance of The Rolling Stones in rock & roll history. The group, which formed in London in 1962, distilled so much of the music that had come before it and has exerted a decisive influence on so much that has come after. Only a handful of musicians in any genre achieve that stature, and the Stones stand proudly among them.

Every album the group released through the early Seventies – from The Rolling Stones in 1964 to Exile on Main Street in 1972 — is essential not simply to an understanding of the music of that era, but to an understanding of the era itself. In their intense interest in blues and R&B, the Stones connected a young American audience to music that was unknown to the vast majority of white Americans. Though the Stones were not overtly political in their early years, their obsession with African American music – from Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf to Chuck Berry, Marvin Gaye and Don Covay – struck a chord that resonated with the goals of the civil rights movement. If the Stones had never made an album after 1965 they would still be legendary.

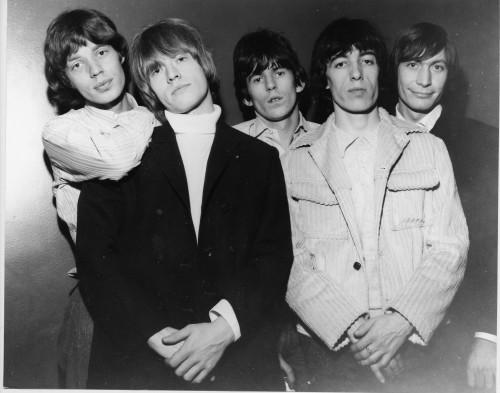

Soon, of course, the Stones – singer Mick Jagger, guitarists Keith Richards and Brian Jones, bassist Bill Wyman and drummer Charlie Watts, in those days – became synonymous with the rebellious attitude of that era. Songs like “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Gimme Shelter” captured the violence, frustration and chaos of that era. For the Stones, the Sixties were not a time of peace and love; in many ways, the band found psychedelia and wide-eyed utopianism confusing and silly. The Stones always were – and continue to be – tough pragmatists. Against the endless promises of Sixties idealism the Stones understood that “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” You simply want to Let It Be? Why not Let It Bleed?

For those reasons, as the Sixties drained into the Seventies, the Stones went on a creative run that rivals any in popular music. Beggars Banquet (1968), Let It Bleed (1969), Sticky Fingers (1971) and Exile on Main Street (1972) routinely turn up on lists of the greatest albums of all time, and deservedly so. All done with American producer Jimmy Miller – “in incredible rhythm man,” in Richards’ terse description – those records shake like the culture itself was shaking. As the Stones were working on Let It Bleed, Brian Jones died, and the band replaced him with Mick Taylor, a guitarist whose lyricism and melodic flair counterbalanced Richards’ insistent, irreducible rhythmic drive, adding an element to the band’s sound that hadn’t been there before, and opening fertile new musical directions.

After that, the Stones were an indomitable force on the music scene, and they have continued to be to this day. In 1978, the band’s album, Some Girls, rose to the challenge of punk (“When the Whip Comes Down”) – whose energy and attitude the Stones had defined a decade earlier – but also swung with the sinuous grooves of disco (“Miss You”). The album is one of the best of that decade. Meanwhile, guitarist Ron Wood had replaced Mick Taylor in 1975, adding another key element to the version of the Rolling Stones that would last another three decades – and counting.

Tattoo You (1981) added the classics “Start Me Up” and “Waiting on a Friend” to the Stones’ repertoire, and took its prominent place among the Stones’ most compelling – and most popular – later albums. Possibly the most underrated album of the Stones’ career, Dirty Work finds the band at its rawest and most rhythmically charged, a reflection of the tumult within the band when it was recorded. True Stones fans have long worn their appreciation of Dirty Work as a hip badge of honor.

With the release of Steel Wheels in 1989, the Stones went back on the road again for the first time in seven years and inaugurated the latest phase of the band’s illustrious career. They’ve made strong, credible new albums during this period – Voodoo Lounge (1994), Bridges to Babylon (1997) – along with the excellent live album Stripped (1995) and the fun, satisfying hits collection, Forty Licks (2002).

More significantly, though, the Stones have set a standard for live performance during this time. That is an achievement completely in accord with the band’s history. When the Stones began to be introduced on their 1969 tour as “The Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World,’ they were staking that claim on the basis of their live performances. It was almost fashionable for bands to withdraw from the road at that time – Bob Dylan and the Beatles had both done so. But the Stones set out to prove that writing brilliant songs and making powerful records did not mean that you were too lofty to get up in front of your fans and rock them until their bones rattled. The Stones’ live shows – epitomized, of course, by Jagger’s galvanizing erotic choreography – had earned the band its reputation in its earliest years, and that flame was being rekindled.

It was lit again twenty years later, and it’s burning still. Since 1989 the Stones have toured every few years to ecstatic response. Bassist Darryl Jones, who had formerly played with Miles Davis, joined the band in 1994, replacing Bill Wyman, and the Stones turned what could have been a setback into a rejuvenating rush of new energy. The Stones’ live success during this period is not a matter of dollars or box-office breakthroughs, though the band has enjoyed plenty of both. It’s about demonstrating a vital, ongoing commitment to the idea that performing is what keeps a band truly alive.

And that’s the critical misunderstanding of the question, “Is this the last time?” that has been coming up every time the Stones have toured for close to forty years now. It’s true that over the decades the Stones have been in the news for many reasons that have little to do with music – arrests, provocative statement, divorces, affairs, all the usual detritus of a raucous lifetime in the public eye. And there’s no doubt that Mick Jagger is as famous a celebrity as the world has ever seen.

But, for all that, the Stones are best understood as musicians, and their own acceptance of that fact is what has enabled them to carry on so well for so long. For all the tabloid headlines, Mick Jagger is finally an extraordinary lead singer and one of the most riveting performers – in any genre – ever to set foot on a stage. Keith Richards is the propulsive engine that drives the Stones and makes their music instantly recognizable. Ron Wood is a guitarist who has formed a rhythmic brotherhood with Richards, but who also colors and textures the band’s songs with deft, melodic touches. And Charlie Watts, needless to say, is one of rock’s greatest drummers. He is both the rock that anchors the band, and the force that swings it. At once elegant in their simplicity and soaring in their impact, none of his gestures are wasted, all are necessary. He and Darryl Jones enliven the often-monolithic notion of the rock & roll rhythm section with an irresistible, unpretentious, jazz-derived sophistication.

Musicians live and create in the moment, and that’s why fans still go see the Stones. Certainly there’s also a catalogue of songs that only a handful of artists could rival. Surely there’s also the desire to encounter a band that has played a pristine role in defining our very idea of what rock & roll is. But seeing the Rolling Stones live is to see a working band playing as hard as they can, and there’s no last time for that.

-Anthony DeCurtis